ROS on DDS

This article was written at a time before decisions were made to use DDS and RTPS as the underlying communication standards for ROS 2. For details on how ROS 2 has been implemented, see the Core Documentation

This article makes the case for using DDS as the middleware for ROS, outlining the pros and cons of this approach, as well as considering the impact to the user experience and code API that using DDS would have. The results of the “ros_dds” prototype are also summarized and used in the exploration of the issue.

Authors: William Woodall

Date Written: 2014-06

Last Modified: 2019-07

Terminology:

- Data Distribution Service (DDS)

- Real-Time Publish Subscribe (RTPS)

- The Object Management Group (OMG)

-

OMG Interface Description Language (IDL) Formal description

Why Consider DDS

When exploring options for the next generation communication system of ROS, the initial options were to either improve the ROS 1 transport or build a new middleware using component libraries such as ZeroMQ, Protocol Buffers, and zeroconf (Bonjour/Avahi). However, in addition to those options, both of which involved us building a middleware from parts or scratch, other end-to-end middlewares were considered. During our research, one middleware that stood out was DDS.

An End-to-End Middleware

The benefit of using an end-to-end middleware, like DDS, is that there is much less code to maintain and the behavior and exact specifications of the middleware have already been distilled into documentation. In addition to system-level documentation, DDS also has recommended use cases and a software API. With this concrete specification, third parties can review, audit, and implement the middleware with varying degrees of interoperability. This is something that ROS has never had, besides a few basic descriptions in a wiki and a reference implementation. Additionally, this type of specification would need to be created anyway if a new middleware were to be built from existing libraries.

The drawback of using an end-to-end middleware is that ROS must work within that existing design. If the design did not target a relevant use case or is not flexible, it might be necessary to work around the design. On some level, adopting an end-to-end middleware includes adopting the philosophy and culture of that middleware, which should not be taken lightly.

What is DDS

DDS provides a publish-subscribe transport which is very similar to ROS’s publish-subscribe transport. DDS uses the “Interface Description Language (IDL)” as defined by the Object Management Group (OMG) for message definition and serialization. DDS has a request-response style transport, which would be like ROS’s service system, in beta 2 as of June 2016 (called DDS-RPC).

The default discovery system provided by DDS, which is required to use DDS’s publish-subscribe transport, is a distributed discovery system. This allows any two DDS programs to communicate without the need for a tool like the ROS master. This makes the system more fault tolerant and flexible. It is not required to use the dynamic discovery mechanism, however, as multiple DDS vendors provide options for static discovery.

Where did DDS come from

DDS got its start as a group of companies which had similar middleware frameworks and became a standard when common customers wanted to get better interoperability between the vendors. The DDS standard was created by the Object Management Group, which are the same people that brought us UML, CORBA, SysML, and other generic software related standards. Now, depending on your perspective, this may be a positive endorsement or a negative endorsement. On the one hand you have a standards committee which is perennial and clearly has a huge influence on the software engineering community, but on the other hand you have a slow moving body which is slow to adapt to changes and therefore arguably doesn’t always keep up with the latest trends in software engineering.

DDS was originally several similar middlewares which eventually became so close to one another that writing a standard to unify them made sense. So in this way, even though the DDS specification has been written by a committee, it has evolved to its current form by reacting to the needs of its users. This type of organic evolution of the specification before it was ratified helps to alleviate the concern that the system was designed in a vacuum and that it does not perform well in real environments. There are some examples of committees coming up with well intentioned and well described specifications that nobody wants to use or that don’t meet the needs of the community they serve, but this does not appear to be the case for DDS.

There is also a concern that DDS is a static specification which was defined and is used in “legacy” systems, but has not kept current. This kind of stereotype comes from horror stories about things like UML and CORBA, which are also products of OMG. On the contrary, DDS seems to have an active and organic specification, which in the recent past has added, or is adding, more specifications for things like websockets, security over SSL, extensible types, request and response transport, and a new, more modern C++11 style API specification for the core API to replace the existing C++ interface. This type of evolution in the standard body for DDS is an encouraging thing to observe, and even though the body is relatively slow, as compared to software engineering technology trends, it is evolving to meet demands of its users.

Technical Credibility

DDS has an extensive list of varied installations which are typically mission critical. DDS has been used in:

- battleships

- large utility installations like dams

- financial systems

- space systems

- flight systems

- train switchboard systems

and many other equally important and varied scenarios. These successful use cases lend credibility to DDS’s design being both reliable and flexible.

Not only has DDS met the needs of these use cases, but after talking with users of DDS (in this case government and NASA employees who are also users of ROS), they have all praised its reliability and flexibility. Those same users will note that the flexibility of DDS comes at the cost of complexity. The complexity of the API and configuration of DDS is something that ROS would need to address.

The DDS wire specification (DDSI-RTPS) is extremely flexible, allowing it to be used for reliable, high level systems integration as well as real-time applications on embedded devices. Several of the DDS vendors have special implementations of DDS for embedded systems which boast specs related to library size and memory footprint on the scale of tens or hundreds of kilobytes. Since DDS is implemented, by default, on UDP, it does not depend on a reliable transport or hardware for communication. This means that DDS has to reinvent the reliability wheel (basically TCP plus or minus some features), but in exchange DDS gains portability and control over the behavior. Control over several parameters of reliability, what DDS calls Quality of Service (QoS), gives maximum flexibility in controlling the behavior of communication. For example, if you are concerned about latency, like for soft real-time, you can basically tune DDS to be just a UDP blaster. In another scenario you might need something that behaves like TCP, but needs to be more tolerant to long dropouts, and with DDS all of these things can be controlled by changing the QoS parameters.

Though the default implementation of DDS is over UDP, and only requires that level of functionality from the transport, OMG also added support for DDS over TCP in version 1.2 of their specification. Only looking briefly, two of the vendors (RTI and ADLINK Technologies) both support DDS over TCP.

From RTI’s website (http://community.rti.com/kb/xml-qos-example-using-rti-connext-dds-tcp-transport):

By default, RTI Connext DDS uses the UDPv4 and Shared Memory transport to communicate with other DDS applications. In some circumstances, the TCP protocol might be needed for discovery and data exchange. For more information on the RTI TCP Transport, please refer to the section in the RTI Core Libraries and Utilities User Manual titled “RTI TCP Transport”.

From ADLINK’s website, they support TCP as of OpenSplice v6.4:

https://www.adlinktech.com/en/data-distribution-service.aspx

Vendors and Licensing

The OMG defined the DDS specification with several companies which are now the main DDS vendors. Popular DDS vendors include:

- RTI

- ADLINK Technologies

- Twin Oaks Software

Amongst these vendors is an array of reference implementations with different strategies and licenses. The OMG maintains an active list of DDS vendors.

In addition to vendors providing implementations of the DDS specification’s API, there are software vendors which provide an implementation with more direct access to the DDS wire protocol, RTPS. For example:

- eProsima

These RTPS-centric implementations are also of interest because they can be smaller in scope and still provide the needed functionality for implementing the necessary ROS capabilities on top.

RTI’s Connext DDS is available under a custom “Community Infrastructure” License, which is compatible with the ROS community’s needs but requires further discussion with the community in order to determine its viability as the default DDS vendor for ROS. By “compatible with the ROS community’s needs,” we mean that, though it is not an OSI-approved license, research has shown it to be adequately permissive to allow ROS to keep a BSD style license and for anyone in the ROS community to redistribute it in source or binary form. RTI also appears to be willing to negotiate on the license to meet the ROS community’s needs, but it will take some iteration between the ROS community and RTI to make sure this would work. Like the other vendors this license is available for the core set of functionality, basically the basic DDS API, whereas other parts of their product like development and introspection tools are proprietary. RTI seems to have the largest on-line presence and installation base.

ADLINK’s DDS implementation, OpenSplice, is licensed under the LGPL, which is the same license used by many popular open source libraries, like glibc, ZeroMQ, and Qt. It is available on Github:

https://github.com/ADLINK-IST/opensplice

ADLINK’s implementation comes with a basic, functioning build system and was fairly easy to package. OpenSplice appears to be the number two DDS implementation in use, but that is hard to tell for sure.

TwinOaks’s CoreDX DDS implementation is proprietary only, but apparently they specialize in minimal implementations which are able to run on embedded devices and even bare metal.

eProsima’s FastRTPS implementation is available on GitHub and is LGPL licensed:

https://github.com/eProsima/Fast-RTPS

eProsima Fast RTPS is a relatively new, lightweight, and open source implementation of RTPS. It allows direct access to the RTPS protocol settings and features, which is not always possible with other DDS implementations. eProsima’s implementation also includes a minimum DDS API, IDL support, and automatic code generation and they are open to working with the ROS community to meet their needs.

Given the relatively strong LGPL option and the encouraging but custom license from RTI, it seems that depending on and even distributing DDS as a dependency should be straightforward. One of the goals of this proposal would be to make ROS 2 DDS vendor agnostic. So, just as an example, if the default implementation is Connext, but someone wants to use one of the LGPL options like OpenSplice or FastRTPS, they simply need to recompile the ROS source code with some options flipped and they can use the implementation of their choice.

This is made possible because of the fact that DDS defines an API in its specification. Research has shown that making code which is vendor agnostic is possible if not a little painful since the APIs of the different vendors is almost identical, but there are minor differences like return types (pointer versus shared_ptr like thing) and header file organization.

Ethos and Community

DDS comes out of a set of companies which are decades old, was laid out by the OMG which is an old-school software engineering organization, and is used largely by government and military users. So it comes as no surprise that the community for DDS looks very different from the ROS community and that of similar modern software projects like ZeroMQ. Though RTI has a respectable on-line presence, the questions asked by community members are almost always answered by an employee of RTI and though technically open source, neither RTI nor OpenSplice has spent time to provide packages for Ubuntu or Homebrew or any other modern package manager. They do not have extensive user-contributed wikis or an active Github repository.

This staunch difference in ethos between the communities is one of the most concerning issues with depending on DDS. Unlike options like keeping TCPROS or using ZeroMQ, there isn’t the feeling that there is a large community to fall back on with DDS. However, the DDS vendors have been very responsive to our inquiries during our research and it is hard to say if that will continue when it is the ROS community which brings the questions.

Even though this is something which should be taken into consideration when making a decision about using DDS, it should not disproportionately outweigh the technical pros and cons of the DDS proposal.

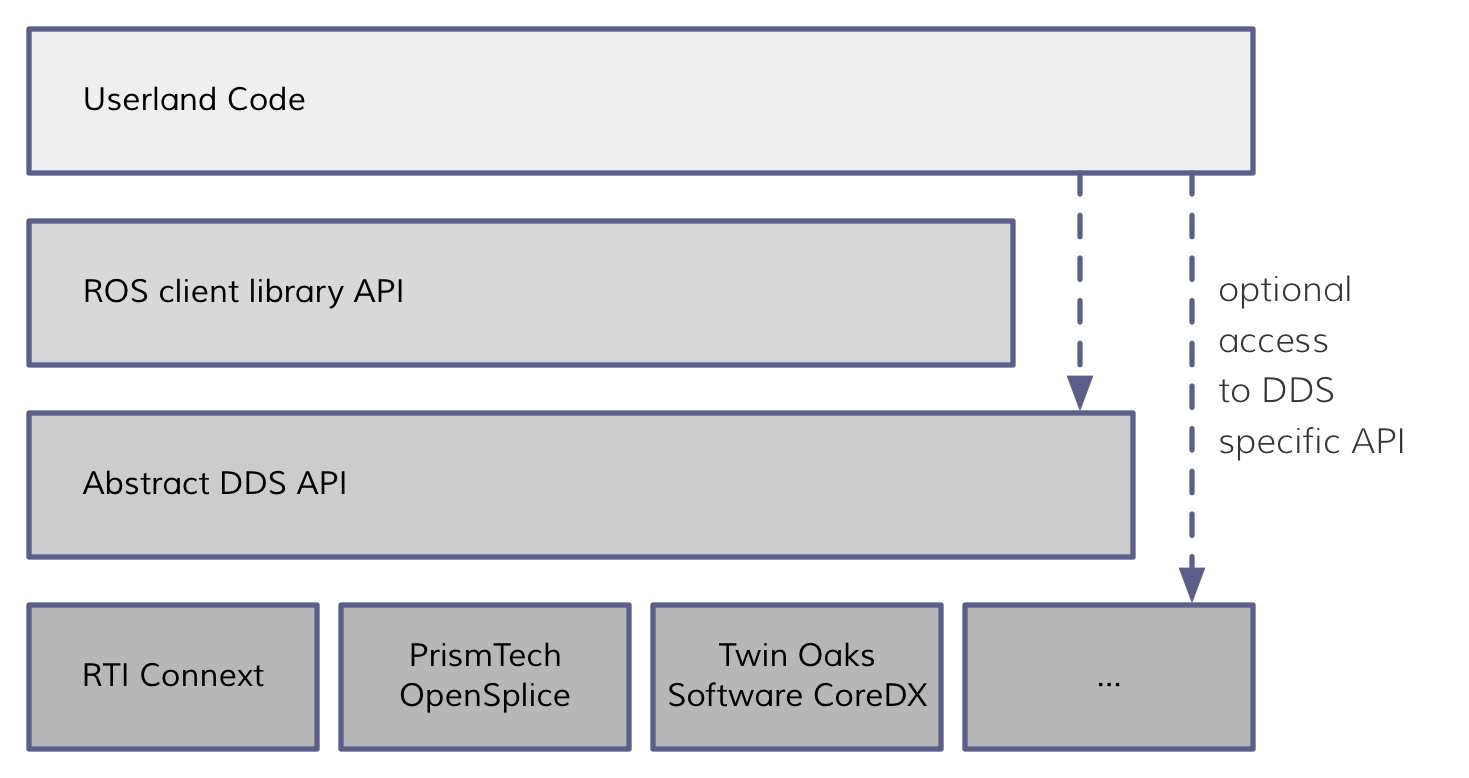

ROS Built on DDS

The goal is to make DDS an implementation detail of ROS 2. This means that all DDS specific APIs and message definitions would need to be hidden. DDS provides discovery, message definition, message serialization, and publish-subscribe transport. Therefore, DDS would provide discovery, publish-subscribe transport, and at least the underlying message serialization for ROS. ROS 2 would provide a ROS 1 like interface on top of DDS which hides much of the complexity of DDS for the majority of ROS users, but then separately provides access to the underlying DDS implementation for users that have extreme use cases or need to integrate with other, existing DDS systems.

DDS and ROS API Layout

DDS and ROS API Layout

Accessing the DDS implementation would require depending on an additional package which is not normally used. In this way you can tell if a package has tied itself to a particular DDS vendor by just looking at the package dependencies. The goal of the ROS API, which is on top of DDS, should be to meet all the common needs for the ROS community, because once a user taps into the underlying DDS system, they will lose portability between DDS vendors. Portability among DDS vendors is not intended to encourage people to frequently choose different vendors, but rather to enable power users to select the DDS implementation that meets their specific requirements, as well as to future-proof ROS against changes in the DDS vendor options. There will be one recommended and best-supported default DDS implementation for ROS.

Discovery

DDS would completely replace the ROS master based discovery system. ROS would need to tap into the DDS API to get information like a list of all nodes, a list of all topics, and how they are connected. Accessing this information would be hidden behind a ROS defined API, preventing the users from having to call into DDS directly.

The advantage of the DDS discovery system is that, by default, it is completely distributed, so there is no central point of failure which is required for parts of the system to communicate with each other. DDS also allows for user defined meta data in their discovery system, which will enable ROS to piggyback higher level concepts onto publish-subscribe.

Publish-Subscribe Transport

The DDSI-RTPS (DDS-Interoperability Real Time Publish Subscribe) protocol would replace ROS’s TCPROS and UDPROS wire protocols for publish/subscribe. The DDS API provides a few more actors to the typical publish-subscribe pattern of ROS 1. In ROS the concept of a node is most clearly paralleled to a graph participant in DDS. A graph participant can have zero to many topics, which are very similar to the concept of topics in ROS, but are represented as separate code objects in DDS, and is neither a subscriber nor a publisher. Then, from a DDS topic, DDS subscribers and publishers can be created, but again these are used to represent the subscriber and publisher concepts in DDS, and not to directly read data from or write data to the topic. DDS has, in addition to the topics, subscribers, and publishers, the concept of DataReaders and DataWriters which are created with a subscriber or publisher and then specialized to a particular message type before being used to read and write data for a topic. These additional layers of abstraction allow DDS to have a high level of configuration, because you can set QoS settings at each level of the publish-subscribe stack, providing the highest granularity of configuration possible. Most of these levels of abstractions are not necessary to meet the current needs of ROS. Therefore, packaging common workflows under the simpler ROS-like interface (Node, Publisher, and Subscriber) will be one way ROS 2 can hide the complexity of DDS, while exposing some of its features.

Efficient Transport Alternatives

In ROS 1 there was never a standard shared-memory transport because it is negligibly faster than localhost TCP loop-back connections.

It is possible to get non-trivial performance improvements from carefully doing zero-copy style shared-memory between processes, but anytime a task required faster than localhost TCP in ROS 1, nodelets were used.

Nodelets allow publishers and subscribers to share data by passing around boost::shared_ptrs to messages.

This intraprocess communication is almost certainly faster than any interprocess communication options and is orthogonal to the discussion of the network publish-subscribe implementation.

In the context of DDS, most vendors will optimize message traffic (even between processes) using shared-memory in a transparent way, only using the wire protocol and UDP sockets when leaving the localhost.

This provides a considerable performance increase for DDS, whereas it did not for ROS 1, because the localhost networking optimization happens at the call to send.

For ROS 1 the process was: serialize the message into one large buffer, call TCP’s send on the buffer once.

For DDS the process would be more like: serialize the message, break the message into potentially many UDP packets, call UDP’s send many times.

In this way sending many UDP datagrams does not benefit from the same speed up as one large TCP send.

Therefore, many DDS vendors will short circuit this process for localhost messages and use a blackboard style shared-memory mechanism to communicate efficiently between processes.

However, not all DDS vendors are the same in this respect, so ROS would not rely on this “intelligent” behavior for efficient intraprocess communication. Additionally, if the ROS message format is kept, which is discussed in the next section, it would not be possible to prevent a conversion to the DDS message type for intraprocess topics. Therefore a custom intraprocess communication system would need to be developed for ROS which would never serialize nor convert messages, but instead would pass pointers (to shared in-process memory) between publishers and subscribers using DDS topics. This same intraprocess communication mechanism would be needed for a custom middleware built on ZeroMQ, for example.

The point to take away here is that efficient intraprocess communication will be addressed regardless of the network/interprocess implementation of the middleware.

Messages

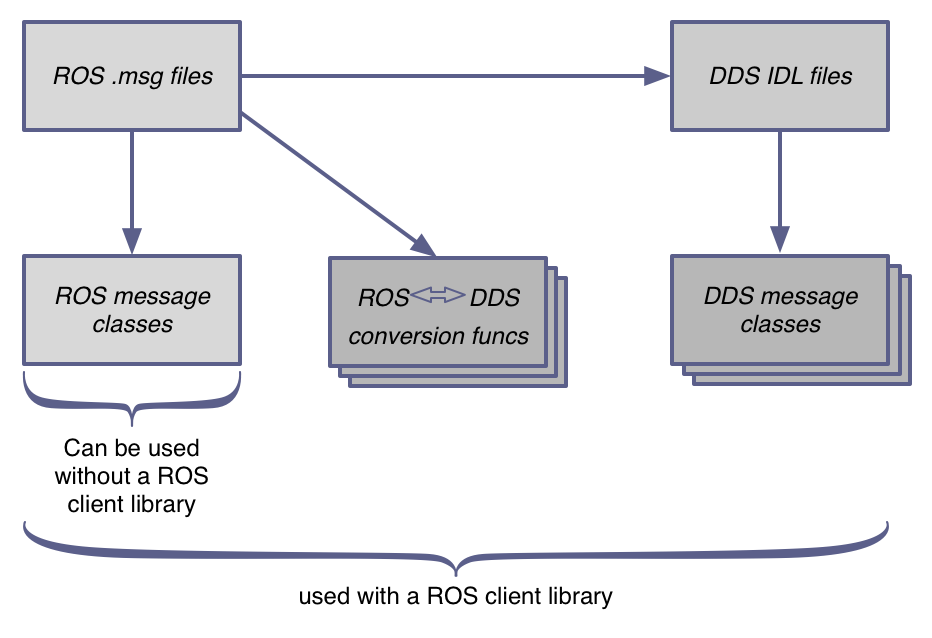

There is a great deal of value in the current ROS message definitions. The format is simple, and the messages themselves have evolved over years of use by the robotics community. Much of the semantic contents of current ROS code is driven by the structure and contents of these messages, so preserving the format and in-memory representation of the messages has a great deal of value. In order to meet this goal, and in order to make DDS an implementation detail, ROS 2 should preserve the ROS 1 like message definitions and in-memory representation.

Therefore, the ROS 1 .msg files would continue to be used and the .msg files would be converted into .idl files so that they could be used with the DDS transport.

Language specific files would be generated for both the .msg files and the .idl files as well as conversion functions for converting between ROS and DDS in-memory instances.

The ROS 2 API would work exclusively with the .msg style message objects in memory and would convert them to .idl objects before publishing.

At first, the idea of converting a message field-by-field into another object type for each call to publish seems like a huge performance problem, but experimentation has shown that the cost of this copy is insignificant when compared to the cost of serialization.

This ratio between the cost of converting types and the cost of serialization, which was found to be at least one order of magnitude, holds true with every serialization library that we tried, except Cap’n Proto which doesn’t have a serialization step.

Therefore, if a field-by-field copy will not work for your use case, neither will serializing and transporting over the network, at which point you will have to utilize an intraprocess or zero-copy interprocess communication.

The intraprocess communication in ROS would not use the DDS in-memory representation so this field-by-field copy would not be used unless the data is going to the wire.

Because this conversion is only invoked in conjunction with a more expensive serialization step, the field-by-field copy seems to be a reasonable trade-off for the portability and abstraction provided by preserving the ROS .msg files and in-memory representation.

This does not preclude the option to improve the .msg file format with things like default values and optional fields.

But this is a different trade-off which can be decided later.

Services and Actions

DDS currently does not have a ratified or implemented standard for request-response style RPC which could be used to implement the concept of services in ROS. There is currently an RPC specification being considered for ratification in the OMG DDS working group, and several of the DDS vendors have a draft implementation of the RPC API. It is not clear, however, whether this standard will work for actions, but it could at least support non-preemptable version of ROS services. ROS 2 could either implement services and actions on top of publish-subscribe (this is more feasible in DDS because of their reliable publish-subscribe QoS setting) or it could use the DDS RPC specification once it is finished for services and then build actions on top, again like it is in ROS 1. Either way actions will be a first class citizen in the ROS 2 API and it may be the case that services just become a degenerate case of actions.

Language Support

DDS vendors typically provide at least C, C++, and Java implementations since APIs for those languages are explicitly defined by the DDS specification. There are not any well established versions of DDS for Python that research has uncovered. Therefore, one goal of the ROS 2 system will be to provide a first-class, feature complete C API. This will allow bindings for other languages to be made more easily and to enable more consistent behavior between client libraries, since they will use the same implementation. Languages like Python, Ruby, and Lisp can wrap the C API in a thin, language idiomatic implementation.

The actual implementation of ROS can either be in C, using the C DDS API, or in C++ using the DDS C++ API and then wrapping the C++ implementation in a C API for other languages. Implementing in C++ and wrapping in C is a common pattern, for example ZeroMQ does exactly this. The author of ZeroMQ, however, did not do this in his new library, nanomsg, citing increased complexity and the bloat of the C++ stdlib as a dependency. Since the C implementation of DDS is typically pure C, it would be possible to have a pure C implementation for the ROS C API all the way down through the DDS implementation. However, writing the entire system in C might not be the first goal, and in the interest of getting a minimal viable product working, the implementation might be in C++ and wrapped in C to begin with and later the C++ can be replaced with C if it seems necessary.

DDS as a Dependency

One of the goals of ROS 2 is to reuse as much code as possible (“do not reinvent the wheel”) but also minimize the number of dependencies to improve portability and to keep the build dependency list lean. These two goals are sometimes at odds, since it is often the choice between implementing something internally or relying on an outside source (dependency) for the implementation.

This is a point where the DDS implementations shine, because two of the three DDS vendors under evaluation build on Linux, OS X, Windows, and other more exotic systems with no external dependencies. The C implementation relies only on the system libraries, the C++ implementations only rely on a C++03 compiler, and the Java implementation only needs a JVM and the Java standard library. Bundled as a binary (during prototyping) on both Ubuntu and OS X, the C, C++, Java, and C# implementations of OpenSplice (LGPL) is less than three megabytes in size and has no other dependencies. As far as dependencies go, this makes DDS very attractive because it significantly simplifies the build and run dependencies for ROS. Additionally, since the goal is to make DDS an implementation detail, it can probably be removed as a transitive run dependency, meaning that it will not even need to be installed on a deployed system.

The ROS on DDS Prototype

Following the research into the feasibility of ROS on DDS, several questions were left, including but not limited to:

- Can the ROS 1 API and behavior be implemented on top of DDS?

- Is it practical to generate IDL messages from ROS MSG messages and use them with DDS?

- How hard is it to package (as a dependency) DDS implementations?

- Does the DDS API specification actually make DDS vendor portability a reality?

- How difficult is it to configure DDS?

In order to answer some of these questions a prototype and several experiments were created in this repository:

https://github.com/osrf/ros_dds

More questions and some of the results were captured as issues:

https://github.com/osrf/ros_dds/issues?labels=task&page=1&state=closed

The major piece of work in this repository is in the prototype folder and is a ROS 1 like implementation of the Node, Publisher, and Subscriber API using DDS:

https://github.com/osrf/ros_dds/tree/master/prototype

Specifically this prototype includes these packages:

-

Generation of DDS IDLs from

.msgfiles: https://github.com/osrf/ros_dds/tree/master/prototype/src/genidl -

Generation of DDS specific C++ code for each generated IDL file: https://github.com/osrf/ros_dds/tree/master/prototype/src/genidlcpp

-

Minimal ROS Client Library for C++ (rclcpp): https://github.com/osrf/ros_dds/tree/master/prototype/src/rclcpp

-

Talker and listener for pub-sub and service calls: https://github.com/osrf/ros_dds/tree/master/prototype/src/rclcpp_examples

-

A branch of

ros_tutorialsin whichturtlesimhas been modified to build against therclcpplibrary: https://github.com/ros/ros_tutorials/tree/ros_dds/turtlesim. This branch ofturtlesimis not feature-complete (e.g., services and parameters are not supported), but the basics work, and it demonstrates that the changes required to transition from ROS 1roscppto the prototype of ROS 2rclcppare not dramatic.

This is a rapid prototype which was used to answer questions, so it is not representative of the final product or polished at all. Work on certain features was stopped cold once key questions had been answered.

The examples in the rclcpp_example package showed that it was possible to implement the basic ROS like API on top of DDS and get familiar behavior.

This is by no means a complete implementation and doesn’t cover all of the features, but instead it was for educational purposes and addressed most of the doubts which were held with respect to using DDS.

Generation of IDL files proved to have some sticking points, but could ultimately be addressed, and implementing basic things like services proved to be tractable problems.

In addition to the above basic pieces, a pull request was drafted which managed to completely hide the DDS symbols from any publicly installed headers for rclcpp and std_msgs:

https://github.com/osrf/ros_dds/pull/17

This pull request was ultimately not merged because it was a major refactoring of the structure of the code and other progress had been made in the meantime. However, it served its purpose in that it showed that the DDS implementation could be hidden, though there is room for discussion on how to actually achieve that goal.

Conclusion

After working with DDS and having a healthy amount of skepticism about the ethos, community, and licensing, it is hard to come up with any real technical criticisms. While it is true that the community surrounding DDS is very different from the ROS community or the ZeroMQ community, it appears that DDS is just solid technology on which ROS could safely depend. There are still many questions about exactly how ROS would utilize DDS, but they all seem like engineering exercises at this point and not potential deal breakers for ROS.